Being passionate about environmental sound art, this post is about providing some insight into some of my own creative processes, but also (and maybe mostly) about spreading knowledge on these sometimes forgotten but fascinating topics.

Wabi-Sabi, Entropy and Acoustic Ecology as both conceptual and practical methods greatly influence my creative thinking: they shine through my sound design and recording approaches when working on personal projects, as well as contribute to give me a sense of artistic direction and intention.

Hopefully the ideas expressed below will help the reader gain a better understanding of my perspective on environmental sound art.

WABI-SABI

(photo credit : Juanjo Ripalda)

*Note : the passages in ‘’brackets’’ in this section of the article are taken from the book Wabi-Sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers

First, let’s talk about Wabi-sabi. If you’ve never heard of it, here is the short version: a Japanese world view celebrating the beauty of things imperfect, impermanent and incomplete. It disregards the grandiose and flawless as aesthetic criteria, and rather looks for unique and unconventional characteristics in humble objects of everyday life. It is the acceptance of things as they are and of the constant motion occurring in nature.

Now for the long version.

Wabi-sabi is the opposite of materialism, of modernism, of stillness, of the spectacular, and of the orderly and the symmetrical.

It is nature-based, and refers to the rustic, the simple, the unsophisticated, and the unpretentious. It concerns the spatial and temporal events and occurrences surrounding us.

(photo credit : Juanjo Ripalda)

In japanese, the meaning of ‘Wabi’ originally bore rather negative connotations regarding poverty and the barbarism that comes with living in remote regions, with few material goods and means. Over time, the evolution of the term transformed into something much more positive, communicating how this type of life away from society and in isolation ‘’fosters an appreciation of the minor details of everyday life and insights into the beauty of the inconspicuous and overlooked aspects of nature’’.

(photo credit : Juanjo Ripalda)

- Nature

Wabi-sabi and nature are intimately related, even though it is possible to observe the philosophy in any environment. It believes in the fundamental uncontrollability of nature, which resonates well with the complementary ideas of chaos, randomness and complex patterns.

In a way, it romanticises nature, calling for a deeper sense of perception than the superficial act of looking. It requires thinking, observation, patience, attention, and care.

It is especially calling attention to natural degradation processes, such as corrosion and contamination. All forms of natural transformation make the expression of wabi-sabi richer.

One of the most important wabi-sabi spiritual values is that truth comes from the observation of nature. The Japanese have suffered extreme natural conditions over time including earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, typhoons, floods, fires, tidal waves, and more, and the wabi-sabi philosophy expresses some of their lessons learned:

- All things are impermanent.

All things, both tangible and intangible, wear down. Permanence can only ever be an illusion.

- All things are imperfect.

Nothing is flawless. So embrace the flaws as unique features, instead of masking them.

- All things are incomplete.

All things, including the universe itself, are in constant, never-ending state of becoming or dissolving. The notion of completion has no basis in wabi-sabi.

(photo credit : Juanjo Ripalda)

- Time

The dimension of time, transformation, degradation or metamorphosis are all present in the wabi-sabi philosophy.

It insists on the non everlasting quality of things – To every thing there is a season.

Some of its metaphysical basis include principles such as the idea that ‘’things are either devolving toward, or evolving from, nothingness’’.

Wabi-sabi is about the delicate traces, this faint evidence, at the borders of nothingness. The universe destructs and constructs, evolves and devolves, and nothingness is, unintuitively, alive with possibility, or potential: ‘’In metaphysical terms, wabi-sabi suggests that the universe is in constant motion towards or away from potential’’.

According to the above statement, I find that memories and perception are equally part of the wabi-sabi recurring themes. It is about the subtleties, the non obvious, the once was, the potential to be, the insignificance of us as individuals in the grand scheme of things. Exploring wabi-sabi is exploring the line between construction and deconstruction, evolution and devolution.

(photo credit : Juanjo Ripalda)

- Observation

Wabi-sabi states that ‘’greatness exists in the inconspicuous and overlooked details’’.

It is the opposite of the ideal of beauty as something monumental, spectacular and enduring.

Wabi-sabi is found in nature at moments of inception or subsiding. It is not about the gorgeous flowers, majestic trees or bold landscapes, it’s about the minor and the hidden, the tentative and the ephemeral: things so subtle and evanescent they are invisible to vulgar eyes.

It is quite easy to make a parallel with recording approaches here: consequently to experience wabi-sabi, one has to slow down, be patient, look very closely (or listen), and pay attention to details. Patience is key.

(photo credit: Juanjo Ripalda)

Wabi-sabi also expresses that ‘’beauty can be coaxed out of ugliness’’.

Beauty is a dynamic event that occurs between you and something else. It is an altered state of consciousness, not an absolute. Thus the separation of beauty and non-beauty or ugliness is not in accordance with the wabi-sabi way of thinking.

Again, the parallel is easy to draw – who is to say which sounds are pleasing, which aren’t? Who is to determine what are the universals in beauty? To me, this is a personal, holistic experience, where individual perception plays a significant role. Whatever you capture out there is part of a greater, more intimate moment between you and your subject, and what you find beautiful may not appeal to someone else, but that’s part of what makes your subject unique.

(photo credit : Juanjo Ripalda)

- Natural disorder

Part of the wabi-sabi state of mind is the acceptance of the inevitable, and the appreciation of the evanescence of life. Wabi-sabi serenely contemplates our own mortality and finality, as part of a greater ensemble. Ecosystems are a good demonstration of this mindset: they are continually evolving (not everlasting), transforming, and complex, while their components are ephemeral and incomplete.

Wabi-sabi also celebrates natural degradation and entropy (in an artistic sense). For instance, signs of corrosion are a manifestation of nature following its course. In materials, this translates as the observation of cracks in clay as it dries, the color and textural metamorphosis of metal when it tarnishes and rusts. Those occurrences we are able to witness are a ‘’representation of the physical forces and deep structures that underlie our everyday world’’.

In terms of aesthetics, wabi-sabi always consists of a suggestion of natural processes.

Things wabi-sabi are expressions of time frozen. They are made of materials that are visibly vulnerable to the effects of weathering and human treatment. They record the sun, wind, rain, heat, and cold in a language of discoloration, rust, tarnish, stain, warping, shrinking, shriveling, and cracking. Their nicks, chips, bruises, scars, dents, peeling, and other forms of attrition are a testament to histories of use and misuse.

They are irregular (non repetitive), intimate (observed in proximity), unpretentious, and simple.

(photo credit : Juanjo Ripalda)

One way wabi-sabi translates into my recording approaches is through welcoming accidents and the unplanned. I accept the unexpected and imperfect as part of a greater order, and find the beauty in overlooked details.

For instance, I remember this one day when I did some field recording in a remote forest. It wasn’t a hiking forest, it was an actual wild forest where it is absolutely impossible to set foot in because the ground is either too dense or unsafe. Only one small dirt road was going across it, which allowed me to get closer. I went as far as I physically could in the forest, which was realistically right at the edge of a path. There I set up with my portable recorder, and hit ‘record’. Headphones on, I could hear how alive the forest was. There was a mild breeze, making the tips of the trees dance and creak. Most trees were dry and in pretty rough shape, some bits were falling apart here and there. The entire forest was lamenting, it was really spooky. So I was recording, never wanting to hit ‘stop’ as I was entranced by what I was listening to, and suddenly this ‘accident’ happens. Somewhere not too far, a big heavy branch falls down, totally ruining my set levels. Also I think I shouted a bit, I was totally taken by surprise. But that’s all fine. Because that was part of the moment, the experience, that unique soundscape. I kept all of those recordings.

I have an equally strong attraction to romanticism, which in many ways contradicts the wabi-sabi experience: bold landscapes, mountains, forces of nature and large scale events also fascinate me. But how better to record a mountain and capture the grandiose than seize all of its living components, its motion, its overlooked details, its changes, its gradation and degradation.

ENTROPY

Now, about entropy.

In a scientific sense (and put simply), entropy is the measurement of disorder. It refers to a principle of thermodynamics dealing with energy, considering the amount of unavailable energy in a closed thermodynamic system as a property of its state, i.e. its order or disorder.

In a poetic or artistic sense, it’s the quality of chaos and randomness, it’s the natural decay and transformation of things surrounding us, it’s the appreciation of uncertainty and finality, and the recognition of a tendency for all things to degrade towards nothingness.

I like to marry the concepts of entropy and wabi-sabi through the ideas of the uncontrollability of nature, the construction and deconstruction, and the evolution and devolution of the universe, as well as the idea that all things are in continuous flow (the opposite of stillness).

While wabi-sabi appreciates the patterns in nature, the instability, the overlooked details of natural decay and transformation, entropy reinforces those ideas by affirming the constant movement of things and greater natural forces, and supports those conceptual and metaphysical views by describing perceptible physical phenomenons.

The way this translates into recording or designing approaches can be many. It concerns just as much what you chose to record, how you record it, and what are you going to do with it.

Some recurring themes may include perception of patterns, the passage of time, and the transformation of matter, the exploitation of unplanned behaviours, the unexpected and randomness. There is no exhaustive list of course, and this exploration is not only about the subject but also very much about the process itself.

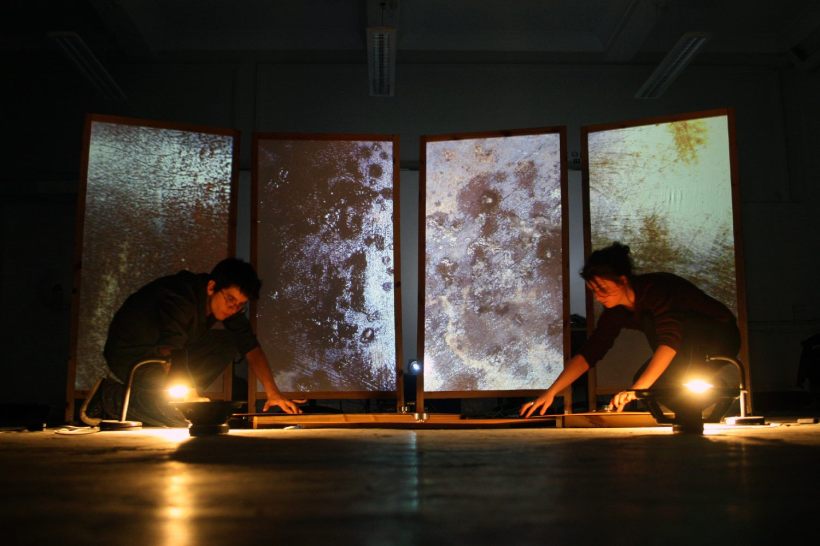

During my Master’s degree at the University of Edinburgh, I participated in creating an audiovisual installation exploring the concept of entropy, along with 4 other extremely talented audio and visual artists (Juanjo Ripalda, Gaby Yanez, Euan McKenzie and Adam Howard).

In this experimental piece, which roughly consisted of a self regulated feedback system played back through rusted metal plates (with audio transducers) and reacting to the space, we communicated the idea of entropy through 6 different levels, as follows:

Level 1 – The rust

We ‘prepared’ 4 large metal plates, making them rust over a period of time, and documented the process through video recording. This is in line with natural decaying processes.

Level 2 – The curves

We modeled formal oxidation measurement curves and implemented them in our installation in such a way that the audio played back would follow these curves in a cyclical nature, thus highlighting the perception of decay over time.

Level 3 – The feedback system

Inspired by composer Agostino Di Scipio, the feedback system is set up according to the notion of ‘audible ecosystems’. This concept illustrates the complexity of the relation between sound and its surrounding environment, and how both interact with each other. It intends to show how any organised system, while being altered by its context and place will ultimately function on its own and potentially lead to unexpected behaviours.

Level 4 – Audio and visual processes

We illustrated entropy’s ‘coloration’ both visually and sonically by playing back the corresponding videos of the metal plates on 4 different screens. Both sound and video were processed in various ways in order to portray digital decay (loss of information, quality degradation, glitches), following the ‘rust curves’ evolution mentioned above.

Level 5 – The human interaction

The human agent contributes to the unpredictable nature of the installation. From the moment interaction occurs, it is impossible to predict how the system will react, change and adjust. Also, as entropy is a process rather than a state or a finality, the concept of interaction emphasizes on the procedure itself rather than the result.

Level 6 – Material

Entropy as a ‘transformation’ was also communicated through the materials chosen as means of display. For instance, audio playback was amplified through mismatched and deteriorated speakers, each of them offering a differently ‘tinted’ sound, spread across the space.

To know more about the installation and watch the recorded performance, you can visit this page.

As you can see, entropy, as any other idea at a conceptual level, can be explored and communicated through various means. The idea is to revisit those concepts and find different ways to present them. I find that making parallels and marrying artistics intentions (such as combining entropy with wabi-sabi and acoustic ecology) is a great way to foster creative ideas and maintain subjects alive – the possibilities are just infinite.

ACOUSTIC ECOLOGY

*Note : the passages in ‘’brackets’’ in this section of the article are taken from the book Environmental Sound Artists: In Their Own Words

The terms (and ideas of) acoustic ecology and soundscape are relatively new. It’s only in the 1970s that these concepts were first introduced, as part of a greater consideration concerning climate change and environmental deterioration.

R. Murray Schafer, in his book The Tuning of the World, wrote that «The soundscape of the world is changing. Modern man is beginning to inhabit a world with an acoustic environment radically different from any he has hitherto known».

His concerns about our sonic environment eventually led to Acoustic Ecology, which is today known as a discipline exploring ‘’the relationship, mediated through sound, between human beings and their environment’’.

Acoustic Ecology is part of a greater environmental sound art movement, consisting of a large body of work, contributing to connect us to the world in a various ways. In order to get a better understanding of the field in general, I’ll weave in some of the defining characteristics of environmental sound art, of which acoustic ecology is a branching creative practice.

Sound art is ‘’ultimately an art form that is inherently diverse, constantly expanding, and conceptually elusive’’. While the purpose and meaning of environmental sound art may very well vary from one artist to another, some characteristics certainly do bind the work of these various artists together. For instance, the strategies of appropriation of structure, processes, materials and impulses derived from the environment around us.

In acoustic ecology, some of the most important points are the following:

- Environment

Sound art from acoustic ecologist can come to life through various ways. From data sonification of natural processes (such as seismic activity – John Bullitt), to playing natural or human made landmarks (Tower Music – Joseph Bertolozzi), or taking advantage of natural forces in order to create musical pieces (Sea Organ – Nikola Bašić), the means are many, but they do have one thing in common: the environment surrounding us. The goals also vary from an effort in raising environmental awareness, an invitation to connect with nature, an exploration of the mathematical patterns that govern our existence, etc, etc. Needless to say, these goals are not mutually exclusive – the intentions can be many.

- The process

There is also a significant appreciation of the process itself just as much as the sonic output that results from it.

In some cases the mere description of the work’s process or structure can be pleasing even without experiencing the work sonically. The ideas themselves can be elegant and intellectually fulfilling.

This makes me think of the fascination I have for the work of experimental composer Iannis Xenakis; while I greatly appreciate his motives, his ideas, his processes and intentions, I am moderately touched by the results of his musical practice. But that doesn’t really matter, because he has inspired me with his creativity either way. To learn more about Xenakis, take a look at this previous post.

- Location

Location and context are of primary relevance in the field of environmental sound art. A strong connection to specific spaces seems to be a unifying thematic thread. ‘’It is the space that brings context to the work’’.

I like this example from Cheryl Leonard, who recorded melting ice from glaciers in Antarctica for her work Meltwater. In many ways, this work is in accordance with both the wabi-sabi philosophy and entropy, in the attention to details and the overlooked, and the small as opposed (or as part of) the grandiose, the natural degradation processes and the changes in states.

«One of the allures of making music out of natural materials and environmental field recordings is delving into the minutia of the very quiet». (Cheryl Leonard)

There are plenty of examples of site specific installations. Some invite to reflect on the spaces and our relationship with them, such as the piece Bivvy Broadcasts by Dawn Scarfe, where real-time audio signal was streamed between a remote forest location and people located in urban areas. This was intended to ‘’reflect on the differences between urban and rural ambience, and to explore the imagined space of the forest as much as the physical reality’’.

Sometimes it’s about finding the musical elements within a natural environment and use them as a basis for creativity, inviting people to find connections with their surroundings and reflect on common interactions with them. (Sounding Underground – Ximena Alarcón, David Rothenberg, Matthew Burtner).

***

Acoustic ecology is known to explore themes centered towards nature and the various socio-political topics and questions surrounding it. Environmental awareness is certainly a common thematic thread, but it would be a misjudgment to reduce the discipline to this particular angle only.

Acoustic ecology is drawn to the principles of design and structure inherent in nature, which presents both orderliness, stability and balance, as well as chaos and randomness. Some elements that can be explored and observed from this complex tapestry are perhaps the mathematical beauty of reiterated forms, the power of repetition, and the forces of physical energy.

For me, all three concepts of acoustic ecology, wabi-sabi and entropy come together to provide a sense of direction and intention. My artistic statement is in accordance with the wabi-sabi philosophy, inclusive of the idea of entropy, and accomplished through the means of acoustic ecology.

I’d like to conclude this article by describing a beautiful sound installation by field recordist and sound artist Chris Watson, one I had the privilege to experience: Hrafn: Conversation with Odin (October 2014).

The installation consisted of a multi-channel, spatialiased sound installation playing back recordings of thousands of ravens returning to roost. The speakers were hidden among the trees, and the audience was taken to the location at twilight to experience the event of the birds arriving and commencing their conversations, culminating into a full raven roost overhead.

Through an intensely immersive perspective, I found that Chris Watson’s work portrayed the metamorphosis of a space, the transformation of an ecosystem, and offered a memory of it. Recorded and natural sounds blended together to form one beautiful audible painting. Many aspects of this installation fell in line with the wabi-sabi philosophy:

- Not materially inclined: hidden speakers, only requires physical presence, the audience sitting on the ground.

- Appreciation of things as they are, no intention to control weather or environment: whatever sound events occurring during the piece were part of it. The ecosystem was alive, while both recorded and natural sounds lived together, then transformed seamlessly into a fully natural soundscape again. The listener could effectively decide when or if the performance was over.

- The evolution from nothingness towards nothingness, the appreciation of finality simply by acknowledging this as a past moment.

- Nature-based reflection: such a piece will inevitable take the listener into a reflection about nature and the environment surrounding us, our relationship with it and its transformation over time.

This installation beautifully incorporates ideas from all 3 concepts I described in this post, and have inspired me to develop similar projects and search for symbiosis between sound art and environment.

I hope this was insightful and inspiring!

Un gros merci pour prendre le temps de partager ta sensibilité!

Je me sens fondamentalement rejoins; ayant un parcours de vie oscillant entre philosophie/art/littérature/musique, chaque fois je me suis retrouvé (du moins en milieu académique) confronté à des approches plutôt de types occidentales (linéaires, ‘in labo’, excessivement rationalisantes/mutilantes),

Les approches plutôt ‘complexes’, ‘in vivo’ ou ‘pragmatiques’ (dans le sens utilisé par plusieurs philosophies orientales) m’apparaissent actuellement beaucoup plus riches, voire beaucoup plus en phase avec la condition humaine telle que je la conçois (soit que selon les contextes/échelles d’observation, des contradictions/aberrations/questions suspendues parfois émergent et laisse l’humain pantois devant son in-omniscience/puissance;

de reconnaître/s’adapter à cette non-Toute-Puissance (aller avec le flow de ce que la nature nous offre comme tu proposes) plutôt que vouloir être maître de tout (et lamentablement s’épuiser/échouer/lutter) est en effet je crois à notre époque une approche en création sonore (et toutes autres formes d’art) *très noble et audacieuse*.

Rafraîchissante.

Bref, encourageant ton article! (je tente tranquillement de me joindre à l’univers des jeux videos/sound design/implémentation, et je cherche à me situer identitairement à ce niveau ces temps-ci, et jcrois éventuellement adopter une approche similaire à celle que tu partages en chaque aspect)

LikeLike

Merci pour ton commentaire Yannick, heureuse de savoir que l’article t’ait plu! 🙂

LikeLike