In 2018 I gave a presentation at the Montreal International Game Summit (MIGS), about the sound of Shadow of the Tomb Raider. This session was about sharing some sound design strategies to make reality sound more believable or interesting than it actually is, or in other words, to aim for ‘believability’ rather than ‘authenticity’, as was our approach in SOTR.

I decided to put this presentation into text (better late than never..!) simply for the sake of accessibility, and in an effort to share this information as widely as possible.

You can watch the full presentation here.

The following text is basically a transcript of the MIGS presentation and does not include any new information.

***

SECTION 1 – INTRO

My name is Anne-Sophie Mongeau, I am a sound designer at Eidos Montreal [that was true at the time, I am currently Senior Sound Designer at Hazelight in Stockholm], and in this presentation I’m going to tell you about designing the sound of reality in Shadow of the Tomb Raider.

What I mean by designing the sound of reality, is that Tomb Raider is a game environment in which the story may be fictional, but it sources its stylistic references from the real world, as opposed to other genres such as Sci-Fi, or Fantasy, where everything is made up and thought of from scratch, and where every sound is original and belonging to that made up world. In the realistic type of game, what we sound design, are sounds from the real world to start with, according to our expectations of them and how we think they should sound based on our experience of them. In a game such as SOTR, a waterfall is a waterfall, a bird is an actual bird species that exist, a door opening is made from materials and mechanics that are known to us. When we see those visual references, we have expectations, of how they are going to sound.

These expectations are based on our real world experience of these things, but also on our experience of them through other media and other representations, and the cinematic, ‘hollywoodesque’ experience that often surrounds them. Not all of us here have seen actual jaguars, or have been through floods and earthquakes, but we all have some sort of idea of what it might, or even ‘should’ sound like.

So how do we, sound designers, meet these expectations, and walk that fine line between what it actually sounds like in reality (accuracy), and what we want it to sound like, based on ours, and the listeners’, biased expectations. WHILE also offering some originality and character – so not only staying within those expectations but surpassing them. In other words how do we contribute to the immersive, cinematic experience, as well as the storytelling, within a realistic context?

So it’s not because the game genre is ‘realistic’ that the sound design is any less important or any easier to do. Because really, when we talk about the quality of being ‘realistic’ in games and entertainment in general, it means more being believable (or convincing), rather than being strictly authentic or accurate.

So how do we make reality more interesting than it really is?

This can be achieved by putting into practice a few realistic sound design techniques which I will go through in a minute, as well as by identifying and taking advantage of the sound design opportunities that the game offers. A combination of those things will help reinforce a sense of place, immersion, character, uniqueness, and make the whole thing more memorable.

You will notice that a lot of my examples feature ambience sound design, because in Tomb Raider ambience has been a very important feature which provided us with many opportunities to reinforce immersion. Also I left the music playing in my examples because music also plays a role in the soundscape, but I made it deliberately lower in volume because we’re going to focus on the sound design.

SECTION 2 – GENERAL STRATEGIES

Let’s start with general techniques. These are things to keep in mind throughout the project.

These broad strategies (this is not an exhaustive list by the way, these are suggestions) can be used at different moments and in different contexts within the game. They have the specific purpose of reinforcing a sense of reality, without necessarily relying on reality (or accuracy) itself.

These include :

- Exaggeration

- Evocation

- Worldizing

- Controlling focus

General Strategy 1 – Exaggeration

The title says it all, this strategy is about exaggerating what accuracy would want us to do, in order to compensate for the lack of sensory experience due to not actually being there. Considering that the field of vision is narrowed to the screen space, that the hearing is reduced to whatever sound system the audio is played back through, that you can’t touch or smell your environment, that your body doesn’t feel out of place, this technique’s goal is to rely on the available stimuli to deliver something that is closer to the sensory experience that should be had, by compensation.

For example, here are some screenshots of some of the stunning looking environments in Shadow of the Tomb Raider.

As you can see, even the visuals kind of overcompensate by making everything look absolutely stunning all the time. Our role as sound designers is to support and even enhance those beautiful environments, and sometimes that means cheating a little bit.

I was in the Alps last summer, and I was faced with similarly stunning landscapes.

So I took a moment when I was there to listen to the soundscape around me.

And this is what I heard :

That actually sounds pretty good, doesn’t it? And it feels nice as well. There is one good reason for it: because this is not actually what I heard. This is designed reality. Now this is what I actually recorded:

This, in the context of a game, would be quite disappointing, and underwhelming. This is why our Peruvian jungle sounds like this:

I’ve actually never been in the Peruvian jungle, but I like to imagine that this is what it sounds like. This is my expectation of it, at least, it’s how I want it to sound like.

This ambience has been ‘cheated’ in different ways. In this environment, every single sound source has been placed by hand, every bird, insect, tree creak and foliage rustle or rain drops. There is no stereo or quad ambiences, everything has its determined 3D place. I will talk a bit more about this later in the sound design opportunities. For now you get the idea about exaggeration. Make it sound better than what a scientific recording would sound like.

General Strategy 2 – Evocation

Next strategy, evocation.

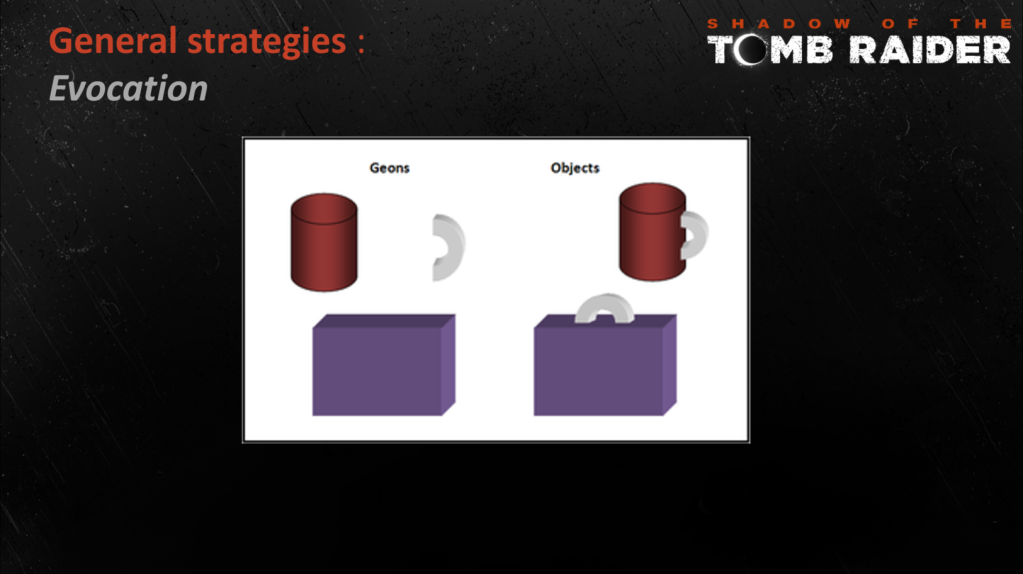

Without digging too deep into cognitive functions, using the power of evocation is a way to build unique character by relying on associations made within one scene and the connections that exist between the different elements in it. For me it seems to have something to do with pattern recognition, somewhat like the psychology theory called recognition-by-components, but extended to the auditory senses rather than only limited to visual stimuli.

This theory says we are able to recognize objects by separating them into geons, which are the object’s main component parts as you can see here.

But if start replacing the individual parts by geons that are somewhat to the outer limits of recognizable patterns, to the point that if I disconnect them they barely make any sense on their own, for instance if I do this :

This weird thing:

Plus this other weird thing:

Which are 2 barely recognizable objects, when put together, become something we can finally identify:

(It’s a weird mug).

As long as I keep them together, I can still identify the whole as something that makes sense.

And it’s not only a mug, but a very unique and original mug.

The whole helps us make sense of the individual parts. Sometimes that means we can take some freedom in the sounds that we use, as long as they make sense within the whole. So using certain sounds that are evocative rather than purely descriptive or scientifically accurate, allows us to offer something that has more of a unique character, and even gives us an opportunity to represent not only the visual and descriptive characteristics of a scene, but also its psychological quality and tone, its mood.

For example in the following area:

There is a large metallic structure, part of a dig site, that descends into this cavernous hole, through which Lara will go and find that it’s a bit of a horror scene. So the atmosphere we want to create here is not only one of a cave, but one of mystery, unease, apprehension. So basically it’s not only the physical characteristics that we are trying to depict through the sound design, but also the emotional ones.

I felt like this situation called for this type of evocative sound design strategy, so I used a recording a made with contact microphones of rain falling on a metallic fence. On its own, it’s not something you would hear in this context as this could not even normally be heard with naked ears. But when you put it in there with the rest, the fact that there is a metallic structure in the scene, and that metal is the main recognisable material in the recording, and because there are other metallic creaks in the soundscape, our brains just make it work by association, and it helps creating a more unique atmosphere rather that simply rely or accurately representing the space as we would hear it in reality.

Listen to the contact mic recording first so you can hear what to listen for in game:

And now watch this video example, which includes this recording in the scene:

So in summary, some abstraction can still feel realistic enough, provided that it is given the right context.

Strategy 3 – Worldizing

Most of you will be familiar with the technique of worldizing. But note that here I am talking about worldizing in the most simple possible way: simply, from the start, record the sounds you need in an environment that is as close as possible as what it is supposed to be in the game, instead of recording only ‘dry’ sound effects and trying to replicate or emulate certain conditions through effects and filters.

For example, I used some recordings of trees creaking in which you can hear a lot of wind, birds, other things as well as a nice natural reverb, and I placed those within the jungle as positional sources, instead of placing only dry, isolated sounds and applying reverb on them, which there are as well, but using a combination can make the whole soundscape more believable.

Listen to the recording first:

And now watch how it sounds in game:

This could be applied to not only ambience but also interactive elements, for example you could have multiple recordings for various types of spaces for things like guns or anything else really.

Strategy 4 – Controlling Focus

In our experiences of the real world, our brains have this ability to focus our auditory attention on a particular stimulus while filtering out a range of other stimuli. This is called the Cocktail Party Effect, and it happens naturally, without us consciously making that effort.

So in a game, so much can be happening at the same time, between ambiences, Foley, music, sound effects, surrounding non important and important VO, and so on, and it’s all concentrated in that screen in front of us, on which we focus our attention. So if we don’t fake that cocktail party effect, it actually ends up sounding less realistic, too chaotic, which doesn’t reflect the way that we would process our surrounding soundscape in reality. So here the goal is the get closer to that sense of realism by cheating and intervening with technology to replicate what we normally do organically.

This can be achieved through:

Azimuth: Make volume curves based on the field of view – which will attenuate the sounds of the sources behind you and bring into focus the ones you are looking at.

Loudness: Making some sounds deliberately louder than they should be so that we can hear them no matter the context, such as making sure you can hear objects that important to the gameplay even through noisy ambiences like thunderstorms.

Ducking: Ducking some sounds when important ones occur so that they seem louder and come through the mix more easily, as we would perceive them to do in real life.

For instance our weapons and explosions duck some of the ambience, SFX and even music so that they have more impact:

SECTION 3 – SOUND DESIGN OPPORTUNITIES

Moving to sound design opportunities, through which all of the strategies mentioned above can be used as well.

Sound design opportunities are moments favorable to feature creative, original, ‘ear-catching’ sound design which will emphasize the emotional qualities that are meant to be transmitted through a particular moment of gameplay.

Those opportunities can arguably be the same whether the game is said to be ‘realistic’ or not, but the sound design strategies that we use in the context of a ‘realistic’ game might differ. In a linear, narrative driven game such as Shadow of the Tomb Raider, these opportunities are many I will go through a few examples.

Sound Design Opportunity 1: Location Reveal

Sound can contribute to emphasize the time and space where the next events are about to take place. It can also be an excellent opportunity to set an emotional tone.

While there is a lot of value in having the soundscape completely interactive and positional, on a location reveal or a vista, ambiences can be faked (scripted) to fit the screen and support the mood, then this faked ambience can disappear gradually and transition to the actual in-game interactive material. This allows more control to choose what kind of material and sentiment to present to the player during their first contact with the space and not leave it to chance.

For example, in this Vista of Paititi, you can hear birds, walla, horns blowing, a lot of liveliness in general, meant to communicate the sense of wonder Lara is feeling when discovering this hidden city for the first time, and taking in the scale of the place and its energy.

Sound Design Opportunity 2: Ambiences

I have a lot to say about ambiences.

In a similar way to location reveals, ambience design can be very useful to reinforce the emotional tone as well as the sense of place, but it is different in a way that instead of being punctual and scripted, ambiences play during long stretches of gameplay during which the narrative development stays relatively the same (the player usually remains within the same environment, exploring or traversing). So the strength of good ambiences is their contribution to a sense of immersion, reinforcing the feeling of actually being there and making the player believe in the environment.

How to achieve that can take many forms:

- Contrast

Emphasize the contrast between one space and another by using different types of assets. For instance even if the geographic location is not far, if the visual and emotional tones are different, the sound must also underline that change. And even if that visual tone would be the same or similar (and probably especially so), sound can really help create the feeling that you are actually in a different place than you were in the previous chapter, and help create new bearings through which the players can locate themselves more easily. In Tomb Raider, our ambience system involved placing by hand every single sound source that were part of the ambiences, there were no quads or 2D ambiences, only positional 3D emitters for every single element constituting the ambiences, this gave us a lot of control over the sense of progression through one space as well as from one space to another.

For instance, one forest can contain a few types of birds species while the other has different ones (even if all of them are said to live in that area),

Or

one forest can be more heavy on birds while the other one is on insects (maybe that says something about humidity and amount of sunlight that penetrates through the trees),

Or

one forest can feel more dense and claustrophobic by placing the sound sources much closer to the player’s path and the other more spacious and wide by placing the sound sources further away with more reverb.

To summarize this point let’s listen to some forest examples taken from the game, they are all in Peru, fairly close to each other, but they all sound quite different depending on the tone.

The first one is meant to be more hostile, dark and claustrophobic, in which Lara is vulnerable :

In this second one Lara goes from a small lush oasis to this forest laced with ruins. She believes she just found the hidden city but (spoiler alert!) she didn’t, in fact she’s about to find it just a bit after that. This space is just abandoned and feels very empty – kind of the underwhelming more realistic version of Paititi that Lara was expecting to find, which itself will contrast with the lively actual Paititi which we have seen in the reveal example earlier.

And finally I have 2 videos showing the same jungle area, but in the first one Lara is about to fight the creature that lives in this part of the forest and terrorizes the wildlife – it’s quiet and creepy. In the second one she killed the creature and the forest has come back to life, all the birds are back and there is even some additional reverb to make it feel even more lush and serene.

Before the fight:

After the fight:

The same strategies can be applied to any type of environment (hubs, puzzles, combat spaces, etc) – simply pinpoint a few elements that are meant to be specific to this place and emphasize on them.

2. Progression

Also, ambiences can greatly contribute to the storytelling and narrative development. Tomb Raider is not really an open world game, even if some hub or exploration areas let you move freely within them. The story takes you from point A to point B, never really looking back. There is rarely any possibility for backtracking, and if there is, you won’t get very far. The story and the game compel you to move forward, so it is important that the sound moves forward and evolves as well with the story and the character. One way to do that is to emphasize on a sense of progression, from the start to the end of the game, but also simply within one space, creating different moods and contrasts.

In this example, Lara goes from a village area to a jungle area, as part of the same general space, and this is where our 3D sources ambience system really helped us: you can hear the various elements of the ambience transform as she walks from one space to the next.

3. Sound design the invisible

Another way to make the most of ambiences as sound design opportunities is to give a story to the various locations, beyond what is visible on screen, and sound design the invisible. In a way you have just heard some of that in the jungle as none of the life we hear is actually seen, we place sound sources without there necessarily being a visual source. But it can go a bit further than that.

For instance, if Lara finds herself in a stone structure like a ruin of a temple which looks like it’s standing pretty still, it is still possible to use sound to reinforce the idea that this structure has been there for thousands of years and is effectively in ruins. For instance by adding some rock rumble and stress, debris falling and crumbling around the place, water drips to indicate that elements have penetrated the outer walls. Also some bats chirping indicating that nature has somewhat overgrown and overtaken the space and claimed it, so that it’s not quite welcoming for human visitors anymore.

It is also possible to use more abstract sounds, which, according to my evocation strategy, will make sense within that greater environment. For instance we have used eerie tones extracted from wooden whistles and flutes or instruments from that region, sounds to which our ears are not quite used to so can’t quite identify, and will blur the line between sound design and music, but will help bring more body to the ambience which might actually be quite dead if we only relied on what should be there to populate it.

In this example Lara moves from a puzzle area inside a temple in ruins, where you can hear fire as it is part of the scene, but beyond that there are some debris sounds, wood rattling in the wind, distant birds that you can hear through the whole in the roof, etc – and in the second part are after the puzzle space, it’s a lot more quiet and some abstract sounds have been placed, all positional, 3D in the scene (there is no actual music).

3. Scripted Events

Moving on to next opportunity: Punctual or interactive scripted events or sequences.

I am talking about an event or a sequence of events that is scripted to happen at some point in the narrative development. These moments are usually quite cinematic and rely on sensation/sensationalism to communicate a sense of drama and excitement to the player.

In the same way camera movements and animations are often created custom to fit certain scripted events, sound should be designed having in mind the purpose of making that sequence stand out from the rest of the ‘systemic’ gameplay. The ways to achieve that highly depend on what the sequence actually is, so I will jump directly to an example :

Throughout this piece of traversal, Lara has to hang on to wooden cages, and ledges breaking under her so it’s full of scripted events:

And another straightforward example of a scripted destruction on Lara’s path:

4. Features and Mechanics

The specific features and mechanics present in a game kind of define the game. They are present throughout the game and constitute the most part of the gameplay experience. Examples include combat, weapons, traversal, underwater traversal, etc.

Each and everyone of these features need to have strong sound design support, reinforcing their respective nature (either aggressive, friendly, fast-pace, adventure, emotionally driven, etc).

In Tomb Raider, traversal is a really important part of the gameplay. This is a good opportunity for sound design to reinforce a sense of adrenaline, danger, vertigo, breathlessness, or even fear when needed.

In this first example, Lara is traversing underwater. Since there is less room for ambience design and moment specific sound design when she is just swimming around, the systemic swim sounds include movements for arms and legs so that as a player with just a controller in our hands we can still feel the motion and the impact or Lara’s movements in her environment.

In this Last example of my presentation, it’s actually a good example of traversal, scripted events and ambiences all in one:

SECTION 4 – CONCLUSION

In summary, in games, and in the broader context of entertainment and immersive media, scientific recordings and ‘accurate’ representations don’t always sound as good as we expect or as we want them to be, and this is where creativity comes in. So in order to deliver a unique, good sounding experience when working on this type of realistic game, the question to ask yourself is: how will you make reality sound better, more exciting, more immersive and more interesting than it really is?

Thank you!